Please Bear with me. I have to go back before getting to my point.

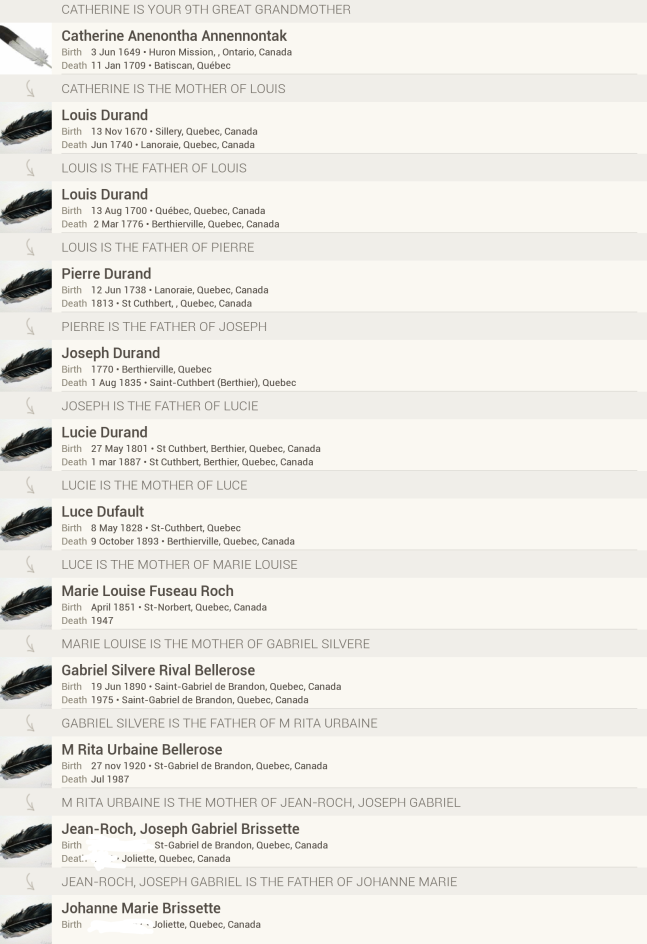

What I have found through my research for empirical evidence to match my oral history of the migration of the first offspring of the unions of First Nations women and Settler men has been posted previously. Here’s a quick overview of timeline:

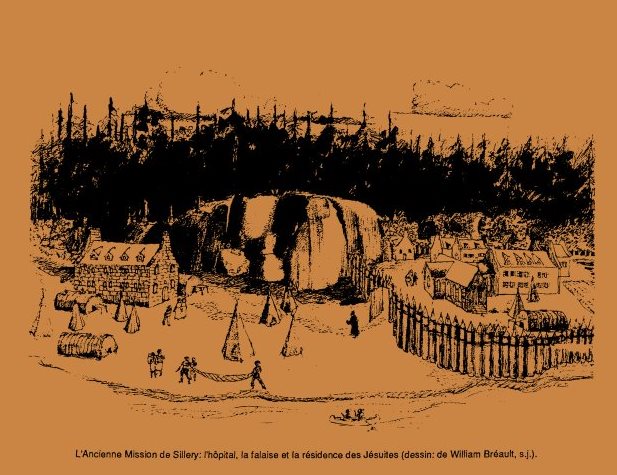

1637 – 1686: Jesuit Mission of Sillery – meeting place of Atikamekw, Abenaki, Innu and refuge of survivors of the Huronia Massacre.

1670 Birth of Louis DURAND, son of Catherine ANENONTA, Attignawantan (Bear Clan) and Jean DURAND, French Settler at Sillery Mission, Québec

1690 Purchase of the Seigneurie des Îles Dupas et du Chicot by Jacques BRISSET et Louis DANDONNEAU, both French Settlers. Louis’ sister Marguerite was Jacques’ wife:

1690 Purchase of the Seigneurie des Îles Dupas et du Chicot by Jacques BRISSET et Louis DANDONNEAU, both French Settlers. Louis’ sister Marguerite was Jacques’ wife:

1696 Louis DURAND travels to Michilimakinac – see more here: The Legend of Louis Durand – is one of the first extensively documented Voyageur. His descendant, also named Louis DURAND, established himself out West, in present day Alberta – see more here: Louis Durand’s Travels

1740 Death of Louis DURAND in Lanoraie, Lanaudière, Québec.

So, that just proves ONE Indigenous ancestor, right? ONE does not make a COMMUNITY, right?

I absolutely agree. Let’s look at other First Nation women and their descendants: (I have more, but unfortunately cannot provide mariage records, or other empirical proof they were from a First Nation community)

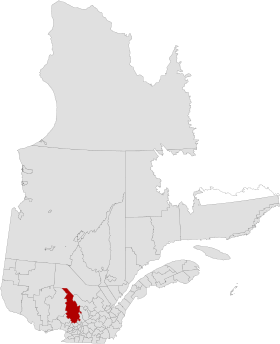

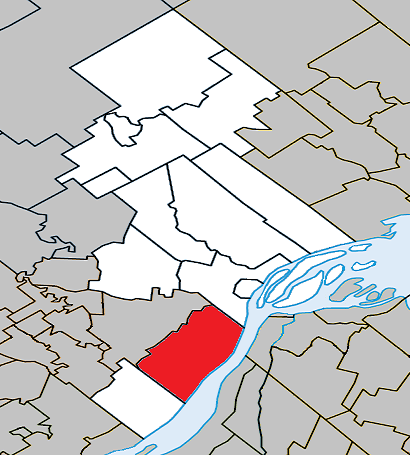

Highlighted below are the communities of (in the order they were occupied by the descendants of these First Nation women) Sorel, Berthierville, Lavaltrie, Sainte-Elisabeth, Saint-Cuthbert, Saint-Norbert, Mandeville and Saint-Gabriel de Brandon.

I haven’t found any empirical proof (yet) explaining how these First Nation women came to be neighbours, despite being from many different First Nations. The mariage records, if found at all, never indicated the names of the unbaptized parents of the First Nation spouse.

All recorded births, mariages and deaths, all contracts and other legal documents were made by men, with men and for men. Under the French Regime, only men could legally transact – it was only in 1976 that women fully gained our Rights under the Quebec Charter of Rights and Freedom.

One thing that seems apparent, is the geographic position of les Îles Dupas et du Chicot, making it the perfect location on the Voyageur hydrographic superhighway linking in all cardinal directions.

My ancestors, Jacques BRISSET and Louis DANDONNEAU, Seigneurs Courchesne and duSablé, appeared to attract many First Nation offspring to the Îles Dupas et du Chicot, and the other neighbouring islands of the Archipelago and linking Nitaskinan -Atikamekw land, Nistassinan -land of the Innu – Wâbuna’ki – land of the Abenaki, Kanien’kehá:ka – land of the Haudenosaunee and Waabanakiing – land of the Anishinaabe.

One thing is for sure when I look at my own First Grandmothers, Métis from Lanaudière are the product of much métissage between many Indigenous Nations.

Blessings of Love and Peace for Ostara, Passover and Easter.

Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ.

I have been writing alot – but mostly in Twitter format at

I have been writing alot – but mostly in Twitter format at