Place d’Armes, aux Trois-Rivières.

Le ministère de la Culture et des Communications du Québec déclare que:

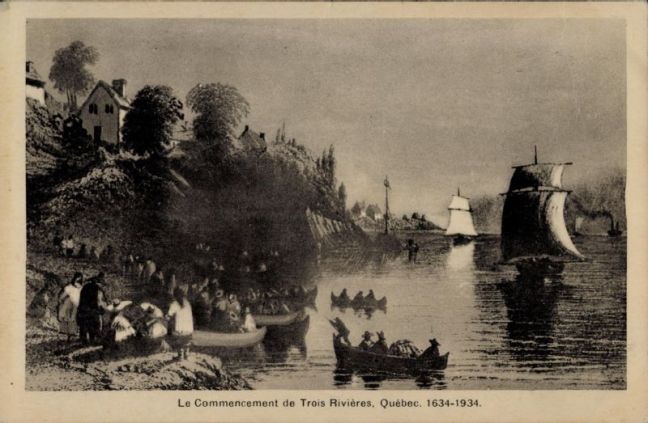

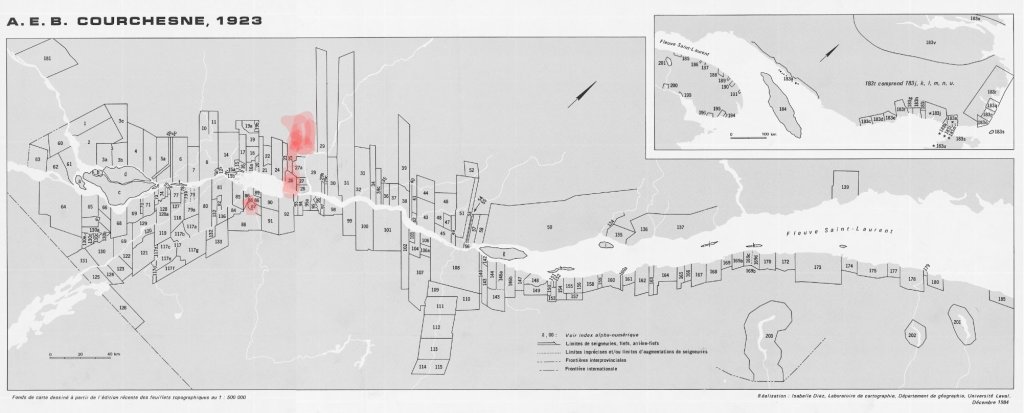

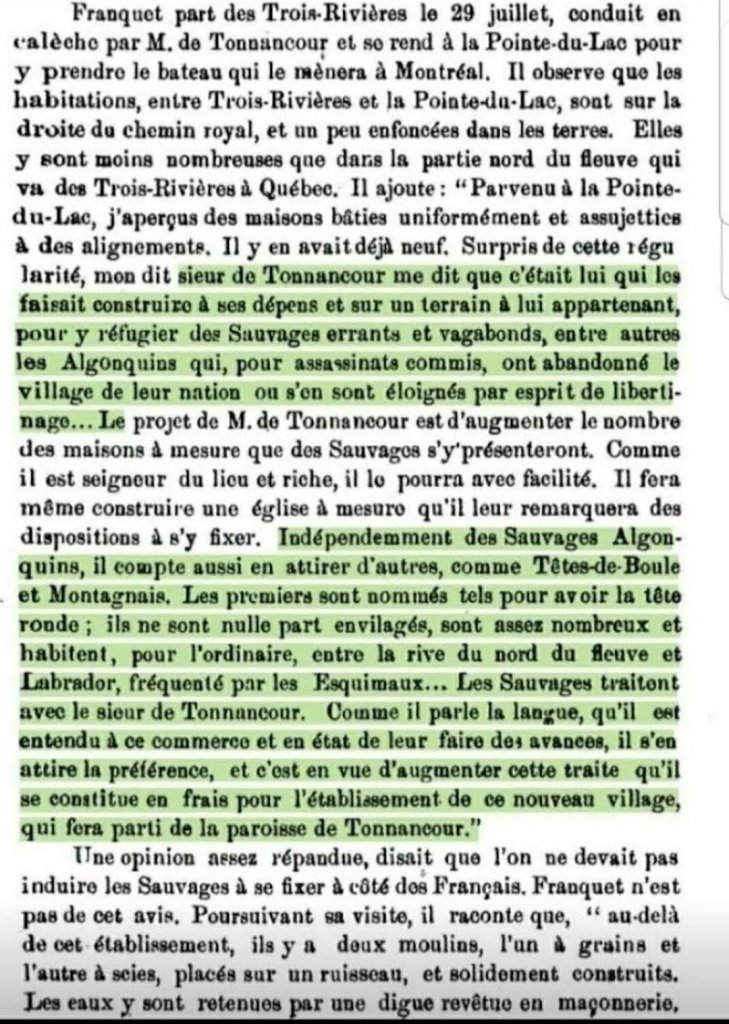

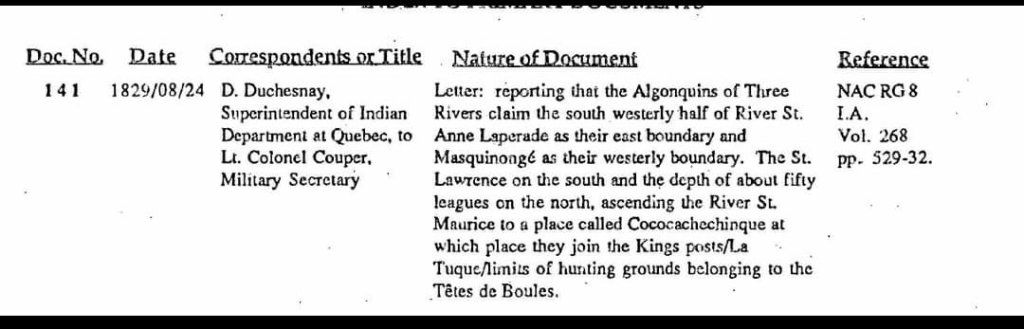

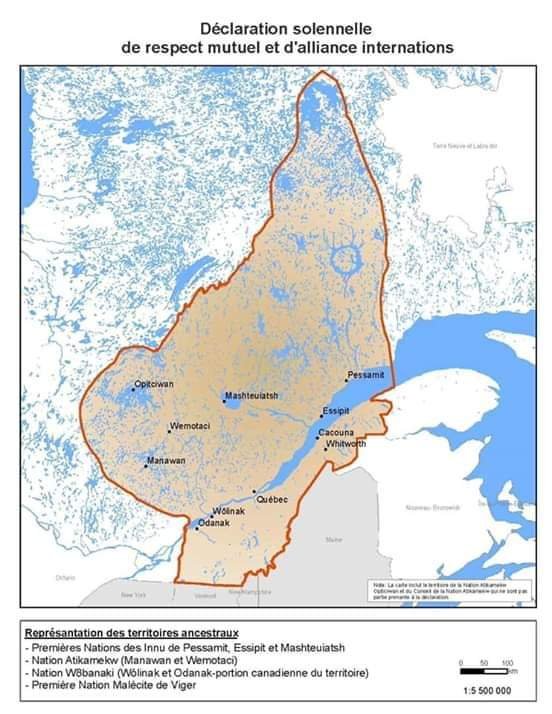

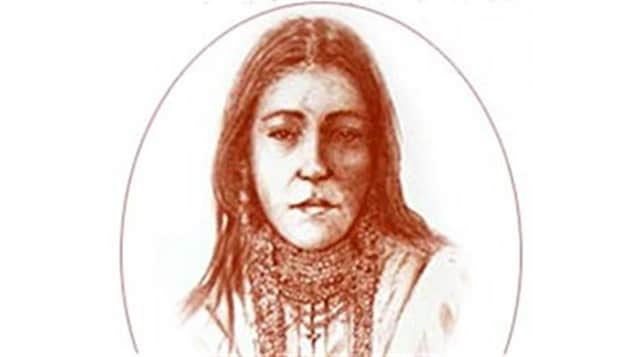

La valeur patrimoniale de la place d’Armes réside dans son intérêt historique. Il reflète le riche passé de la ville de Trois-Rivières et son premier développement urbain. Le fief initial, concédé au chef algonquin Charles Pachirini (Baazhińiniwish) en 1648, est avant tout un campement autochtone. Il est cependant géré par les jésuites qui octroient de petits lots aux colons à partir de 1656 et devient ainsi une demeure française.

En 1722, le terrain est converti en marché public. Devenu une place d’Armes dans la seconde moitié du 18ème siècle, il fut utilisé pour des exercices militaires jusqu’au début du 20ème siècle. Le canon en bronze fabriqué en Russie et découvert en 1828 aurait été rapporté par des soldats de Trois-Rivières ayant participé à la guerre de Crimée (1853-1856). Le site conserve encore le nom de Place d’Armes, bien qu’il soit maintenant utilisé comme parc urbain.

La valeur patrimoniale de la Place d’Armes repose également sur son intérêt pour l’histoire de la conservation du patrimoine au Québec. Contrairement à la “loi sur la conservation des monuments et des œuvres d’art d’intérêt historique et artistique” adoptée en 1922, la “loi sur la conservation des monuments, sites et objets historiques et artistiques”, sanctionnée en 1952, intègre des paysages et des sites de intérêt artistique ou historique dans les biens susceptibles d’être protégés. La place d’Armes, classée en 1960, est le premier lieu protégé au sens de cette loi.

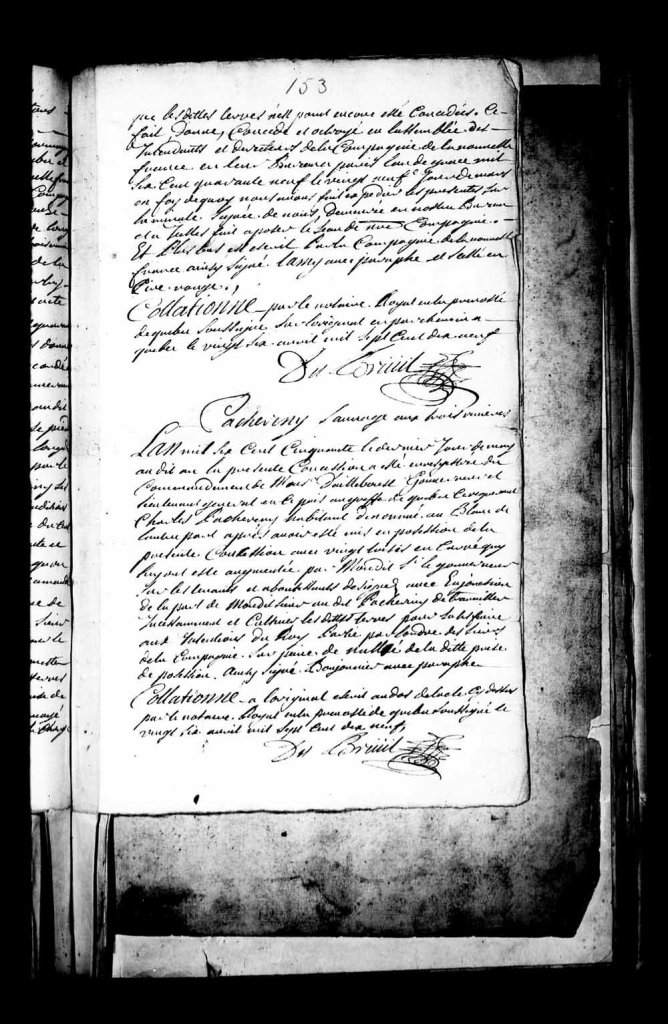

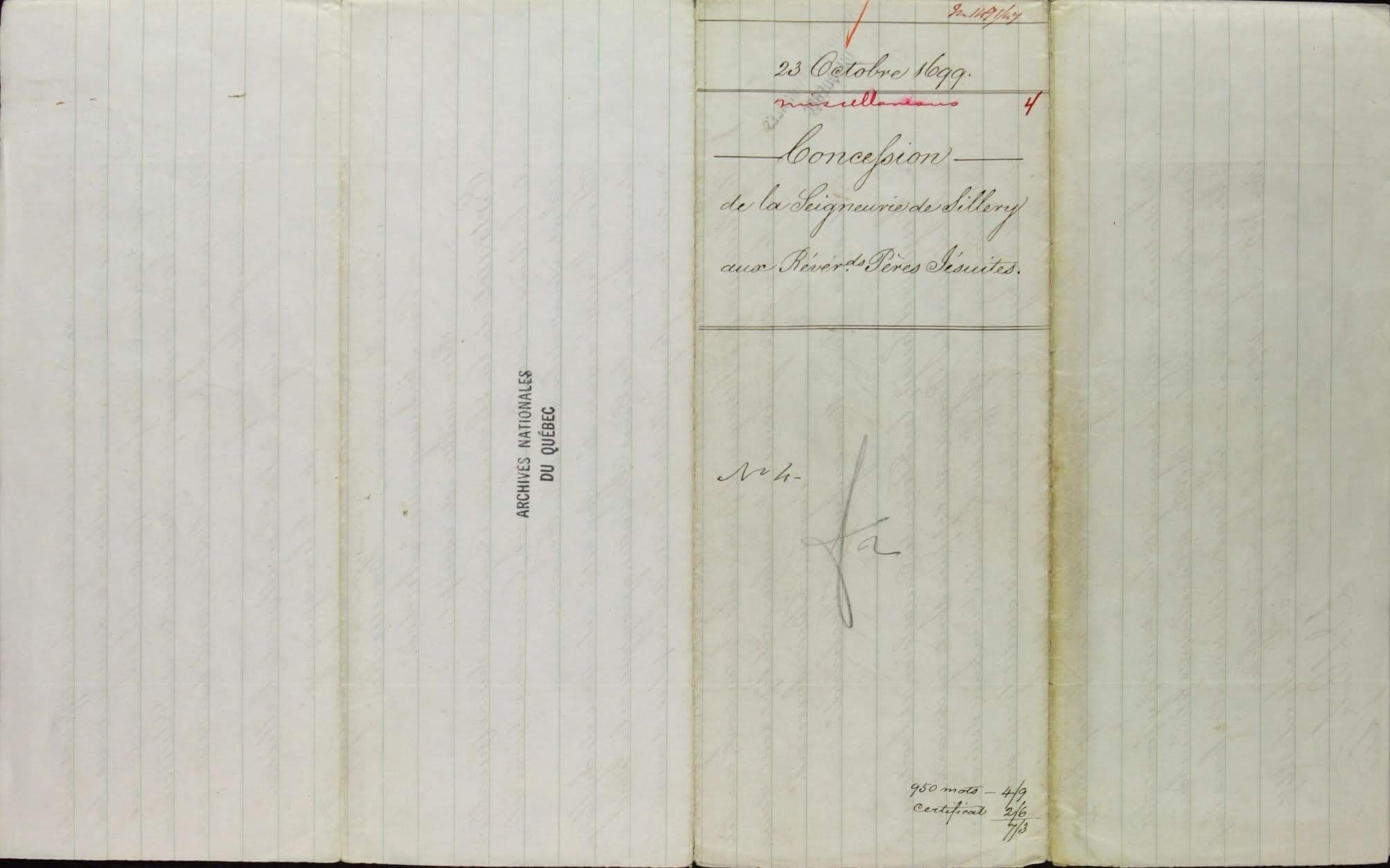

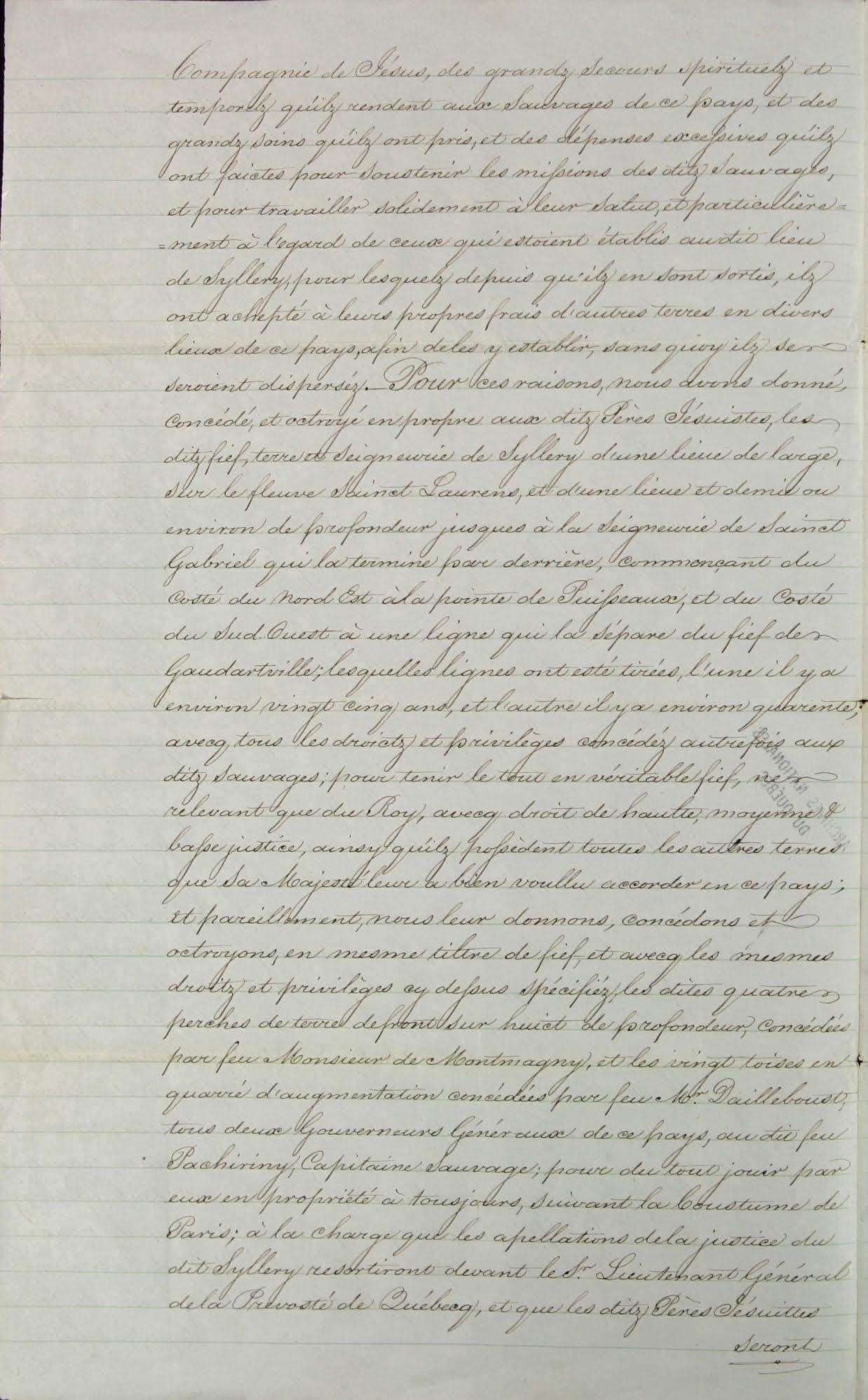

Cependant, dans le contrat de 1699 ci-dessous, nous voyons que la terre a été transférée aux jésuites, sans aucune consultation des peuples autochtones qui avaient occupé la terre:

23 Octobre 1699

Concesfsion

De la Seigneurie de Sillery

Aux Révérends Pères Jésuites

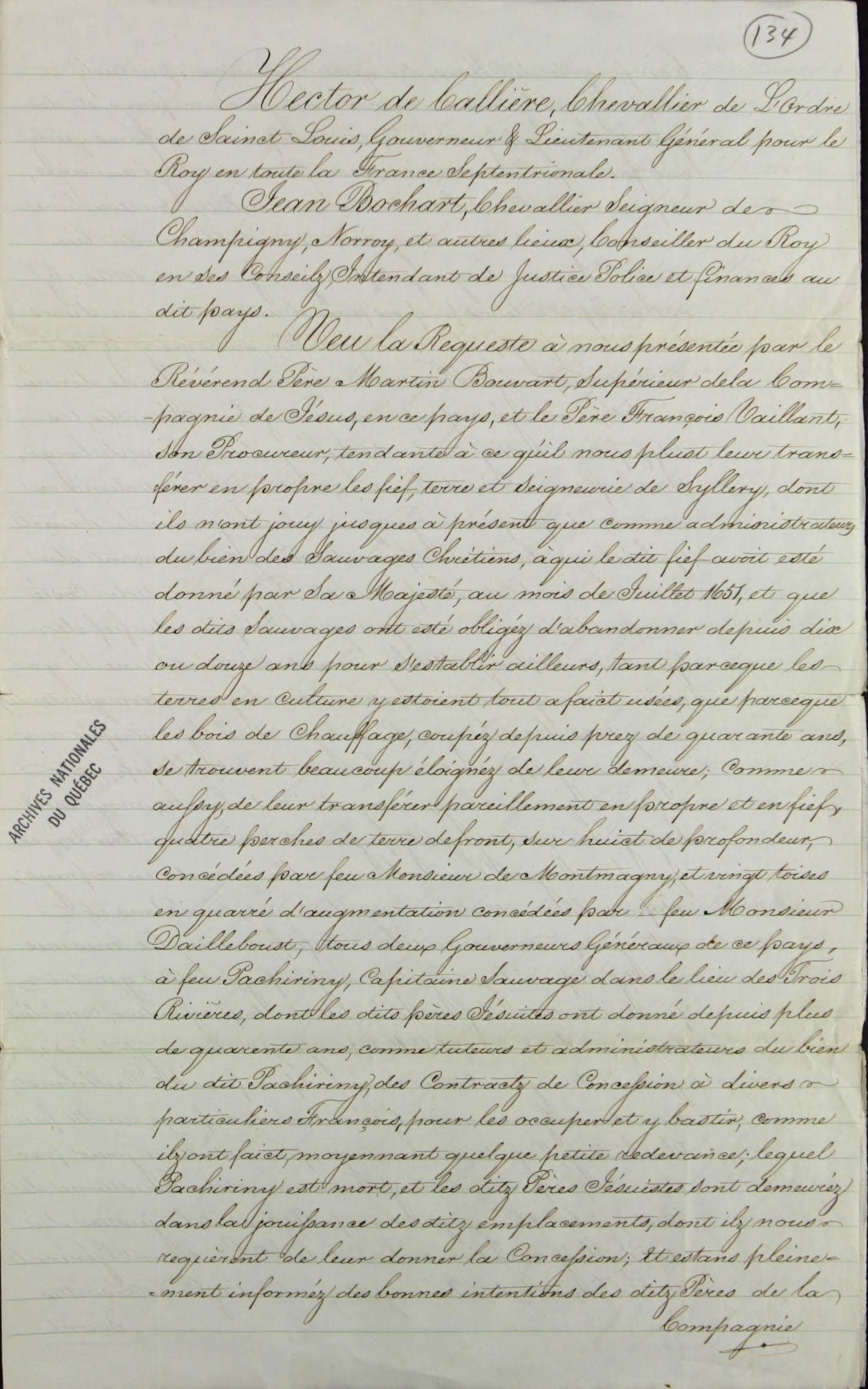

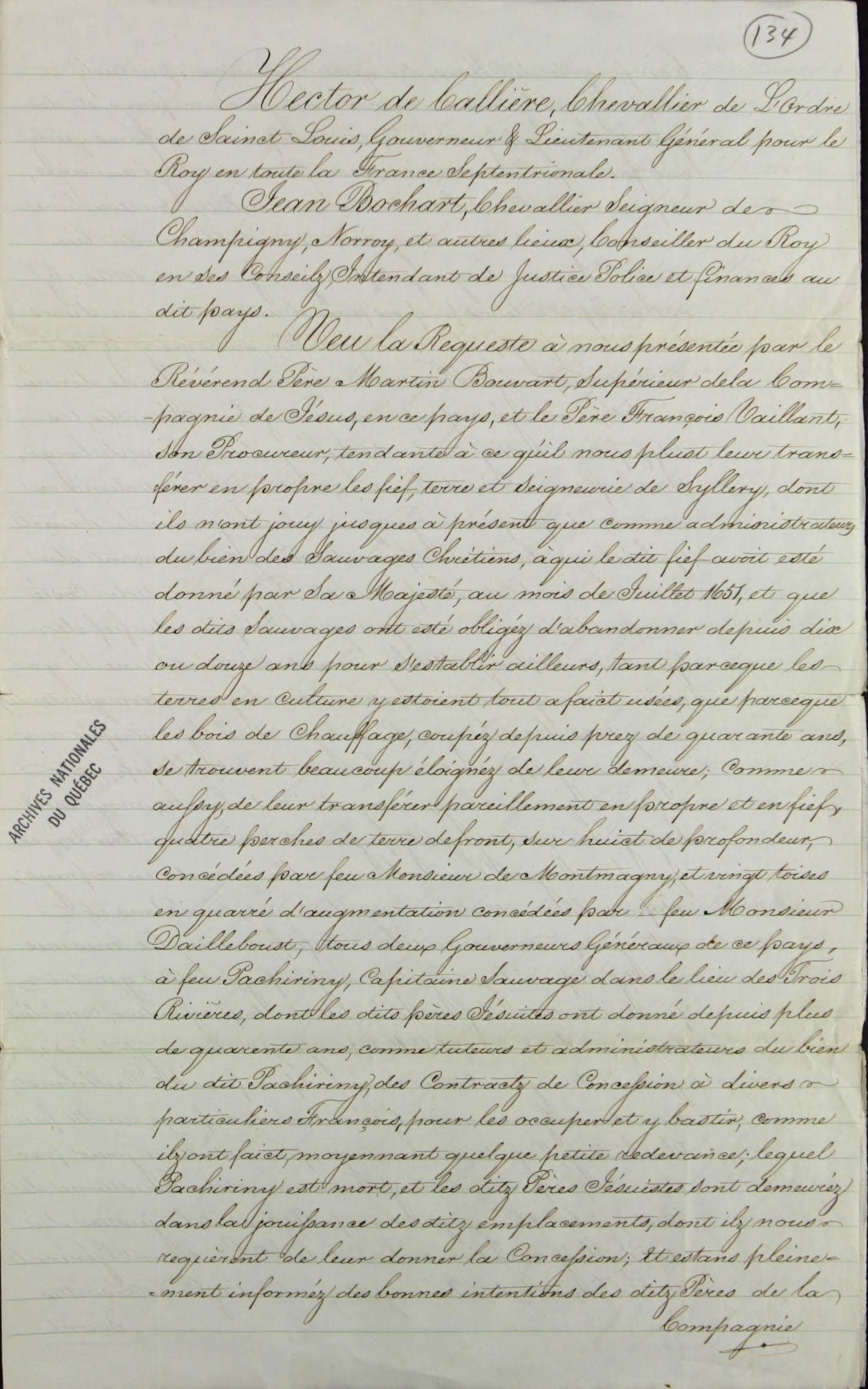

HECTOR de CALLIÈRE, Chevallier de L’Ordre de Sainct Louis, Gouverneur & Lieutenant Général pour le Roy en toute France Septentrionale.

JEAN BOCHART, Chevallier Seigneur des Champigny, Norroy et autres lieux, Conseiller du Roy en ses Conseilz, Intendant de Justice Police et Finances au dit pays.

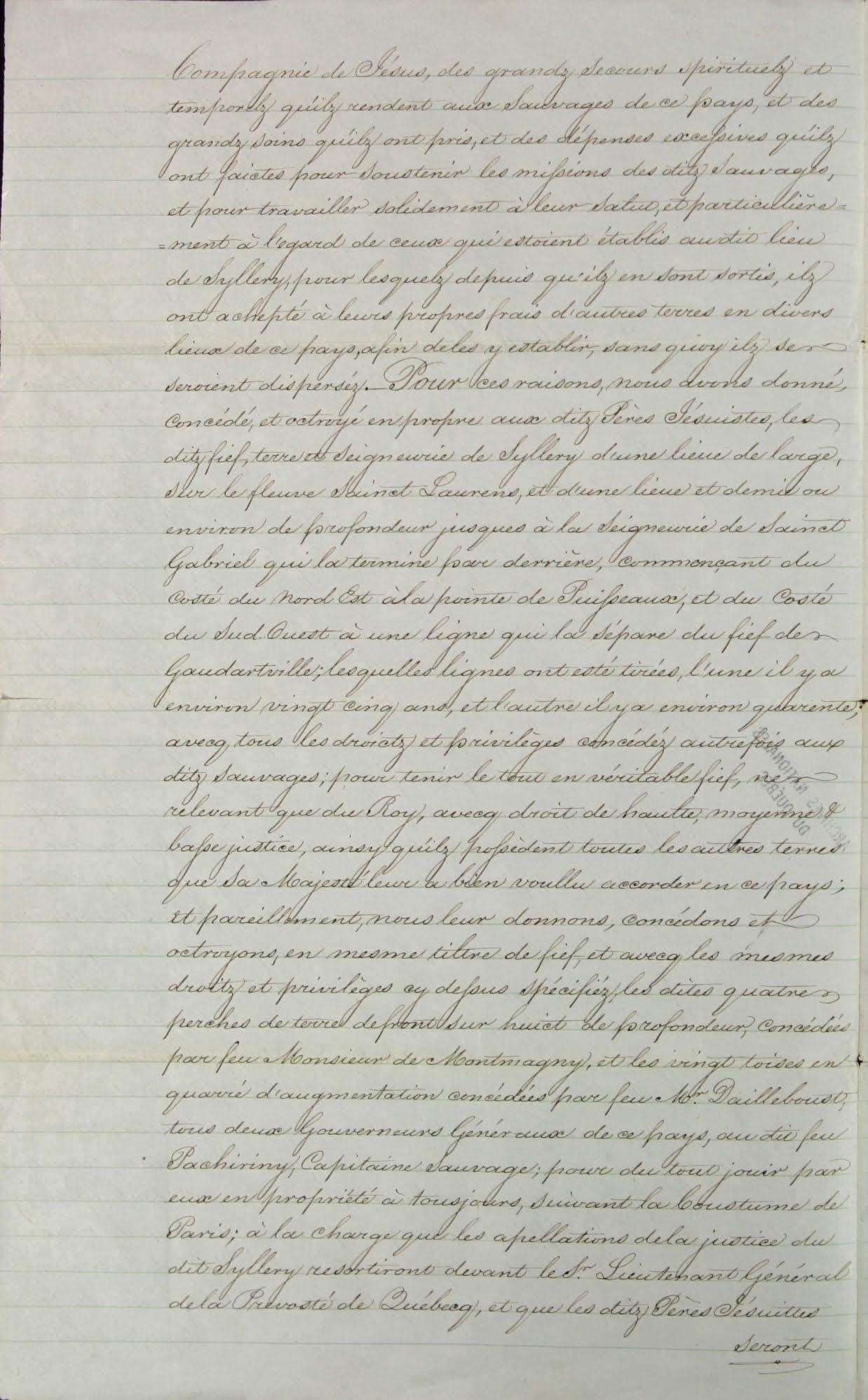

VU LA REQUESTRE à nous présentée par le Révérend Père Martin Bouvart, Supérieur de la Compagnie de Jésus, en ce pays, et le Père François Vaillant, son Procureur, tendante à ce qu’il nous plust leur transférer en propre les fief, terre et Seigneurie de Syllery, donts ils n’on jouy jusques à présent que comme administrateurs du bien des Sauvages Chrétiens, à qui le dit fief avoi testé donné par Sa Majesté, au mois de Juillet 1651, et que les dits Sauvages ont été obligéz d’abandonner depuis dix ou douze ans pour s’establir ailleurs, tant parce que les terres en culture y estoient tout a faict usées, que parceque les bois de chauffage, coupéz depuis prez de quarante ans, se trouvent beaucoup éloignéz de leur demeure, commes au foy, de leur transférer pareillement en propre et en fiefs, quatre perches de terre de front, sur huict de profondeur, concédées par fe Monsieur de Montmagny, et vingt toises en quarré d’augmentation concédées par feu Monsieur Dailleboust, tous deux Gouverneurs Généraux de ce pays, à feu Pachiriny, Capitaine Sauvage dans le lieu des Trois Rivières, dont les dits pères Jésuites ont donné depuis plus de quarante ans, comme tuteurs et adminstrateurs du bien du dit Pachiriny, des contractz de Concefsion à divers particuliers François, pour les occuper et y bastir, comme ilz ont faict, moyennant quelque petite redevance; lequel Pachiriny est mort, et les ditz Pères Jésuites sont demeurez dans la jouifsance des ditz emplacements, dont ilz nous requèrent de leur donner la Concefsion; et estans pleinement informéz des bonnes intentions des ditz Pères de la Compagnie de Jésus, des grands secours spirituelz et temporelz qu’ilz rendent aux Sauvages de ce pays, et des grandz soins qu’ilz ont pris, et des dépenses excefsives qu’ilz ont faictes pour soustenir les mifsions des ditz Sauvages, et pour travailler solidement à leur Salut, et particulièrement à l’égard de ceux qui estoient établis audit lieu de Sillery, pour lesquelz depuis qu’ilz en sont sortis, ilz on achepté à leurs propres frais d’autres terres en divers lieux de ce pays, afin de les y establir; sans quoy ilz se seroient disperséz.

Pour ces raisons, nous avons donné, concédé, et octroyé en propre aux ditz Pères Jésuistes, les dits fief, terre et Seigneurie de Syllery d’une lieue de large, sur le fleuve Sainct Laurens, et d’une lieue et demie ou environ de profondeur jusques à la Seigneurie de Sainct Gabriel qui la termine par derrière, commençant du costé du Nord Est à la pointe de Puifseaux, et du costé du Sud Ouest à une ligne qui la sépare du fief des Gaudartville; lesquelles lignes ont esté tirées, l’une il y a environ vingt cinq ans, et l’autre il y a environ quarante; avecq tous les droictz et privilèges condédéz autrefois aux ditz Sauvages; pour tenir le tout en véritable fief, ne relevant que du Roy, avecq droit de haulte, moyenne & bafse justice, ainsy qu’ilspofsèdent toutes les autres terres que Sa Majesté leur a bien voullu accorder en ce pays; et pareillement, nous leur donnons, concédons et octroyons, en mesme titre de fief, et avecq les mesmes droitz et privilèges cy defsus spécifiéz, les dites quatre perches de terre de front sur huict de profondeur, concédées par few Monsieur de Montmagny, et les vingt toises en quarré d’augmentation concédées par few Mr Dailleboust, tous deux Gouverneurs Généraux de ce pays, au dit feu Pachirini, Capitaine Sauvage, pour du tout jouir par eux en propriété à toujours, en suivant la Coustume de Paris; à la charge que les apellations de la justice du dit Syllery resortiront devant le Sr. Lieutenant Général de la Prevosté de Québecq, et que les ditz Pères Jésuites seront enus de prendre de Sa Majesté ratiffication des présentes dans un an. En témoin dequoy nous les avons signées, à icelles faict apposer les sceaux de nos armes, et contrisigner par nos Sécrétaires. Donné à Québecq, ce vingt troisième Octobre, mil six cent quatrevingt dix neuf.

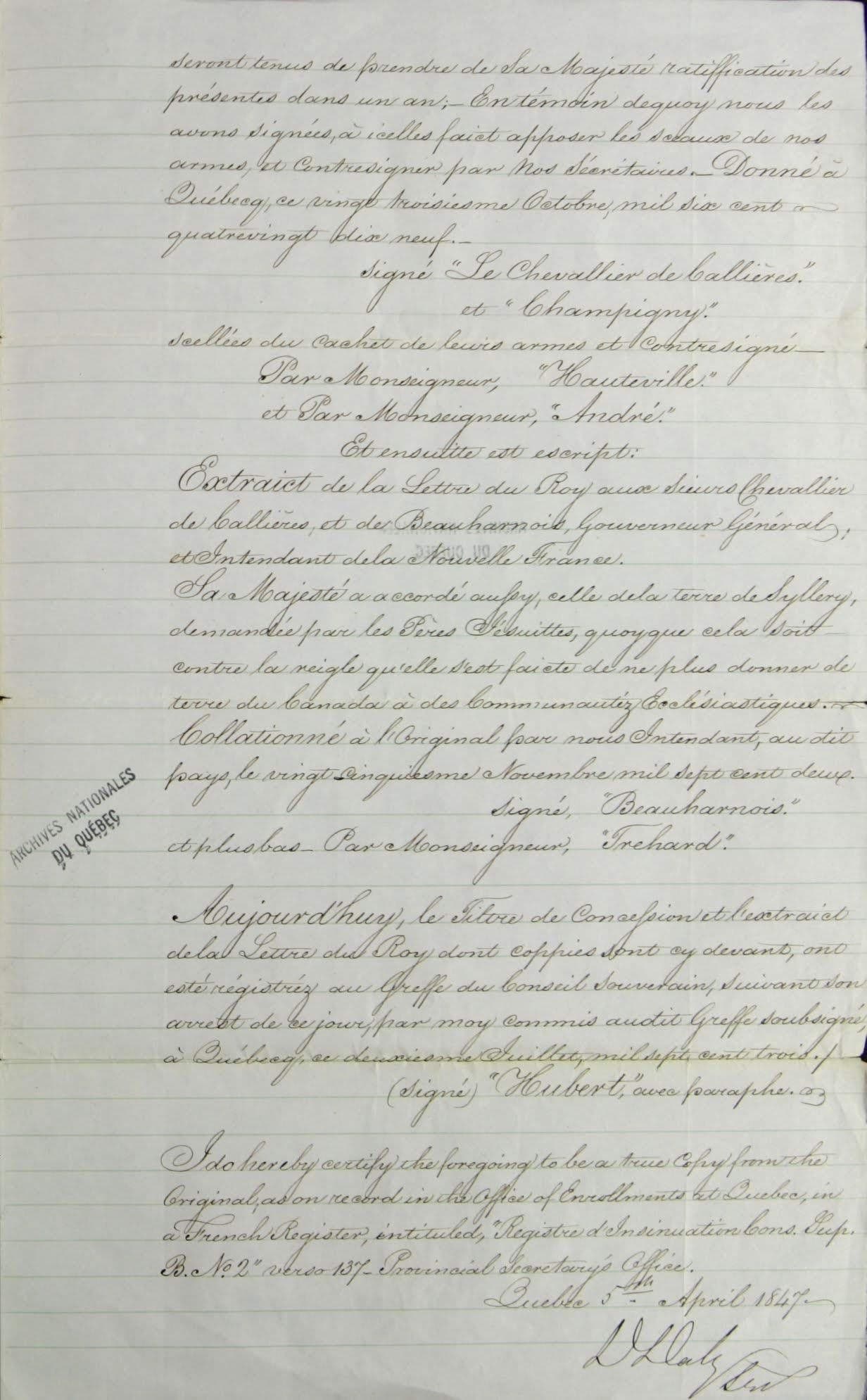

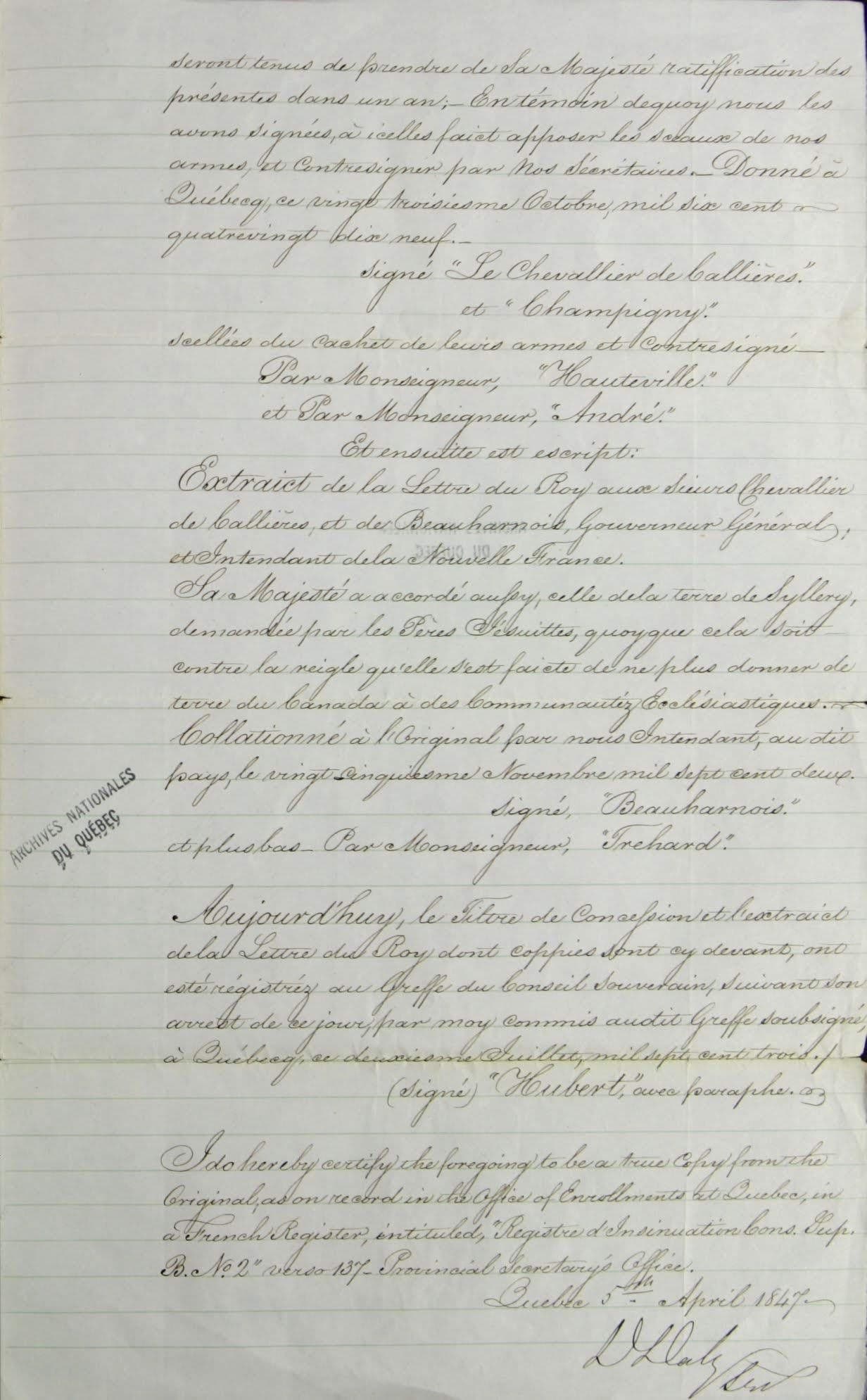

Signé « Le Chevallier de Callières. »

Et « Champigny. »

Scellées du cachet de leurs armes et contresigné

Par Monseigneur, « Hauteville »

Et Par Monseigneur, « André. ».

Et ensuitte est escript :

EXTRAIT de la Lettre du Roy aux Sieurs Chevallier de Callières, et de Beauharnois, Gouverneur Général et Intendant de la Nouvelle France.

Sa Majesté a accordé aufsy, celle de la terre de Syllery, demandée par les Pères Jésuites, quoyque cela soit contre la règle qu’elle s’est faicte de ne plus donne de terre du Canada à des Communautéz Ecclésiastiques.

Collationné à l’Original par nous Intendant, au dit pays, le vingt cinquiesme Novembre mil sept cent deux.

Signé, « Beauharnois. »

Et plus bas Par Monseigneur « Trehard. »

AUJOURD’HUY, le Titre de Concefsion et l’extraict de la Lettre du Roy dont conppies sont cy devant, ont esté régistréz au Greffe du Conseil Souverai, suivant son arrest de ce jour, par moy commis audit Greffe soubsigné à Québec, ce deuxiesme Juillet, mils sept cent trois.

(signé) « Hubert, » avec paraphe

I do hereby certify the foregoing to be a true copy from the original, as on record in the Office of Enrollments at Quebec, in a French Register, intitulated, “Registre d’Insinuation Cons. Sup. B. No.2” verso 137. Provincial Secretary Office.

Quebec 5th of April 1847

DDalz

Sec

Place d’Armes, in Trois-Rivières.

The Quebec Ministry of Culture and Communications, states that:

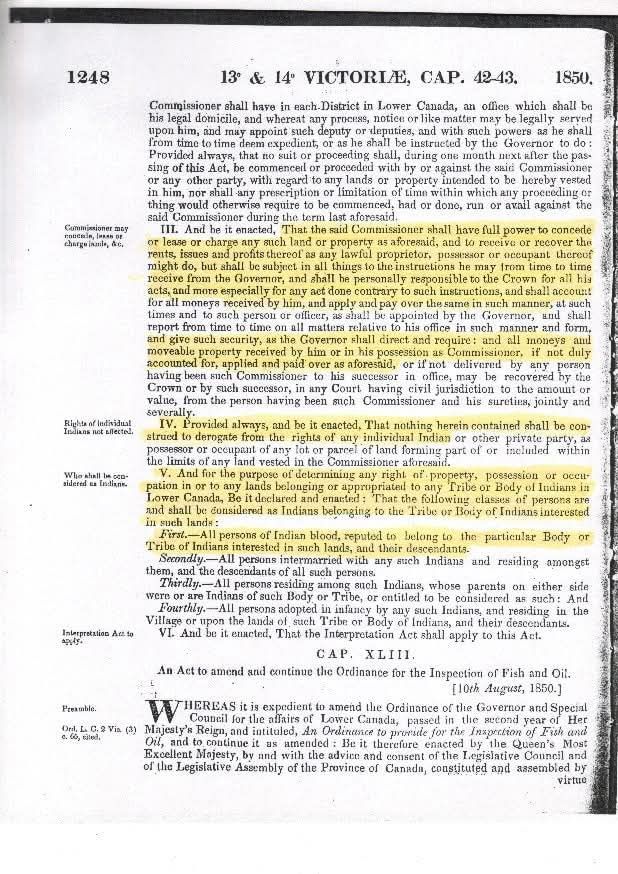

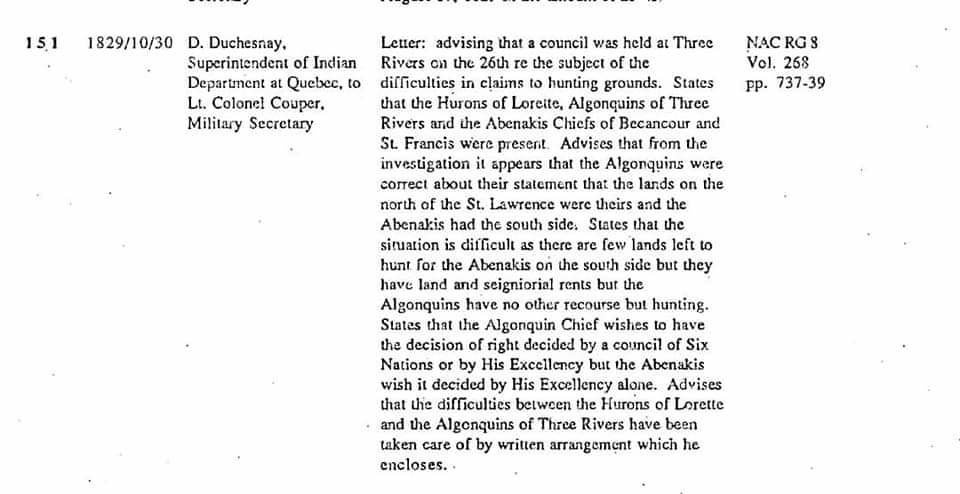

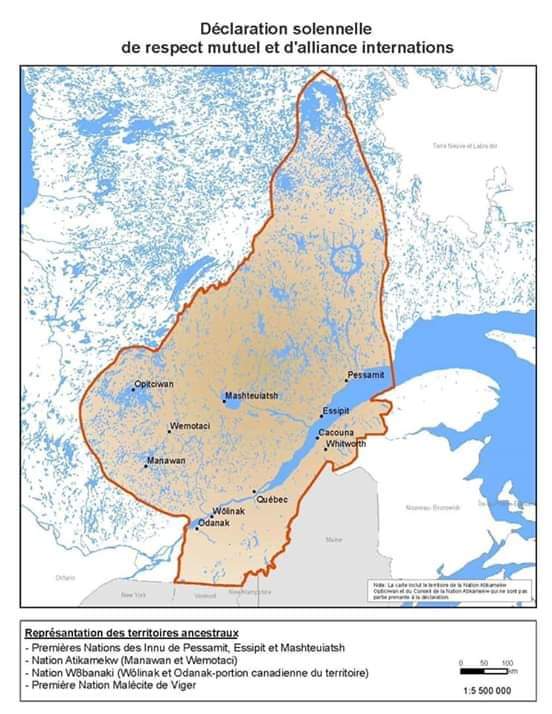

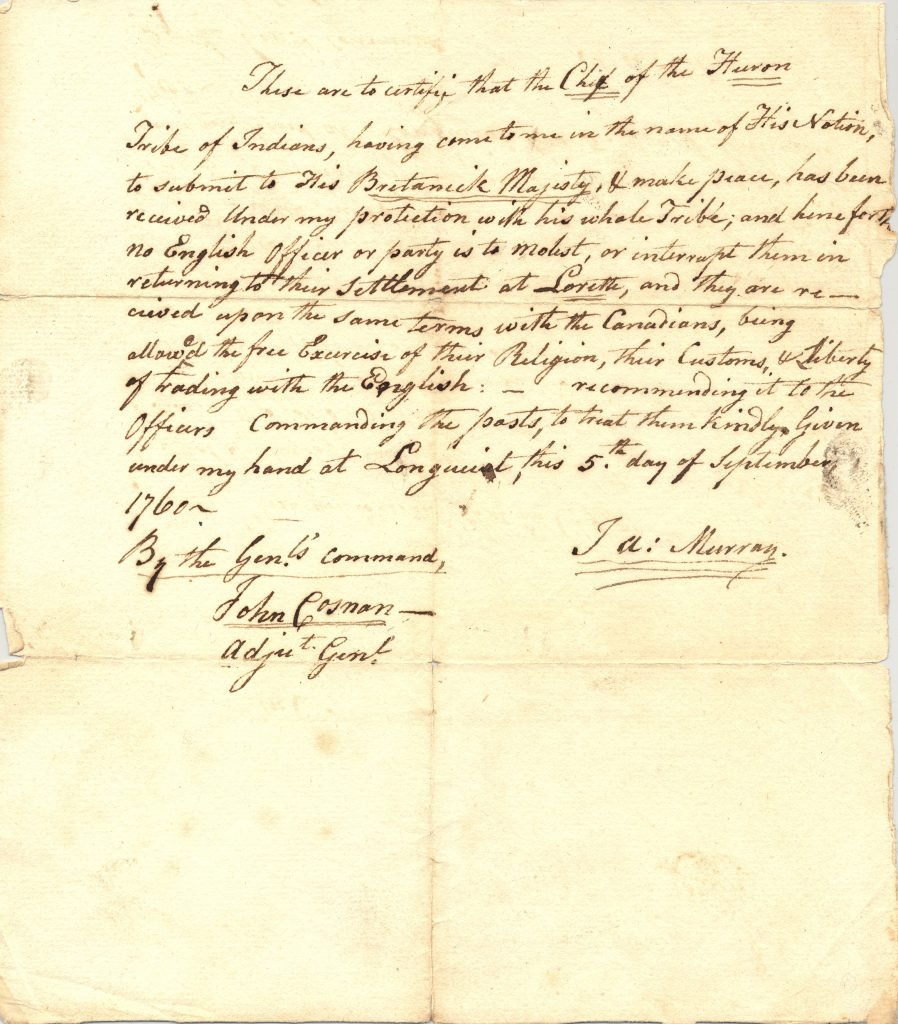

The heritage value of Place d’Armes lies in its historical interest. It reflects the rich past of the city of Trois-Rivières and its first urban development. The initial fief, conceded to the Algonquin Chief Charles Pachirini in 1648, is first of all an Indigenous encampment. It is however managed by the Jesuits who grant small lots to settlers from 1656 and thus becomes a French dwelling place.

In 1722, the land is converted into a public market. Became a place d’Armes in the second half of the 18th century, it was used for military exercises until the beginning of the 20th century. The Russian-made bronze cannon found there, dated 1828, was reported to have been brought back by soldiers from Trois-Rivières who participated in the Crimean War (1853-1856). The site still retains the name Place d’Armes although it is now used as an urban park.

The heritage value of Place d’Armes is also based on its interest in the history of Québec’s heritage conservation. Unlike the “Law on the Conservation of Monuments and Works of Art of Historical and Artistic Interest” adopted in 1922, the “Law for the Conservation of Historic and Artistic Monuments, Sites and Objects”, sanctioned in 1952 integrates landscapes and sites of scientific, artistic or historical interest in the properties likely to be protected. Place d’Armes, ranked in 1960, is the first protected place under this law.

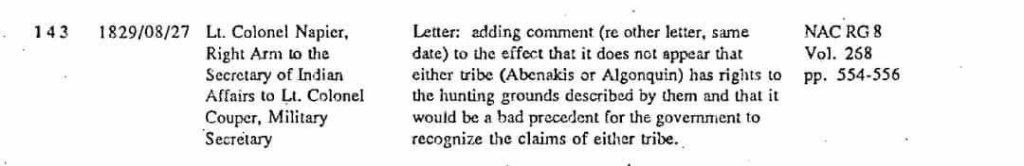

However, buried in this 1699 contract below, we find that the land was transferred to the Jesuits, without any consultation with the Indigenous people who had occupied the land:

October 23, 1699

Concession

of the Seigneurie of Sillery

To the Reverend Jesuit Fathers

HECTOR de CALLIÈRE, Chevallier of the Order of Sainct Louis, Governor & Lieutenant General for the King in all northern France.

JEAN BOCHART, Chevallier Lord of Champigny, Noraie and other places, Councilor of the Kingdom in his Council, Intendant of Justice Police and Finances to the said country.

BY THE REQUEST presented to us by the Reverend Father Martin Bouvart, Superior of the Society of Jesus, in this country, and Father François Vaillant, his Prosecutor, who is eager to see us. Moreover, it pleases us to transfer to them the fiefs, land and lordship of Sillery, which they have enjoyed until present only as administrators of the property of the Christian Savages, to whom the said fief has tested given by His Majesty, in the month of July, 1651, and that the said Savages were obliged to give up ten or twelve years ago to settle elsewhere, both because the cultivated land was quite worn out, and that because firewood, cut for almost forty years, is far away from their homes, as in our faith, to transfer them as their own and in fiefs, eight perches (unit of measure) by four perches deep, conceded by Monsieur de Montmagny, and the addition of twenty squared fathoms conceded by the late Monsieur Dailleboust, both governors general of this country, to the late Pachiriny, Savage Chief in Three Rivers, whose so-called Jesuit fathers given for more than forty years, as tutors and administrators of the land of the said Pachiriny, contract with various private French individuals, to occupy them and to build on them, as they have done, for a small fee; aforementioned Pachiriny is now deceased, and the say Jesuit Fathers are to remain in the enjoyment of the said locations, which we are asked to give them the Concession; and are fully informed of the good intentions of the said Fathers of the Jesus, in recognition of the great spiritual and temporal help which they render to the Savages of this country, and of the grounds the care they took, and the extraordinary expenses they made to support the missions of the Savages, and to work solidly on their salvation, and especially on those who were established in the said place of Sillery, for which since they came out of it, done at their own expense on other lands in various places from this country, in order to establish them there; without which they would have dispersed.

For these reasons, we have given, conceded, and granted to the said Jesuit Fathers, the said fief, land and lordship of Sillery of a league wide, on the Saint Laurence river, and a league and a half or so deep down to the Seigneurie of Saint Gabriel, behind, starting from the northeastern coast at the tip of Ruisseaux, and from the south-west coast to a line that separates it from the fief of Gaudartville; which lines were drawn, one about twenty-five years ago, and the other about forty; with all the rights and privileges once condemned to the said Savages; to hold the whole thing in true fief, falling only to the King, with the right of justice, middle and good justice, as well as all the other lands which his Majesty has been good enough to grant them in this country; and likewise, we give them, concede and grant, in the same title of fief, and with the same right and privileges specified, the so-called four perches of land abreast on the depths of the body of water, conceded by the defunct Monsieur de Montmagny, and the twenty fathoms in square footage conceded by Mr. Dailleboust, both governors general of this country, to the said late Pachirini, Sauvage Chief, to enjoy by all in their property forever, following the Coutume de Paris; to the charge that the appellations of the justice of said Syllery will spring before the Sr. Lieutenant General of the Prevost of Quebecq, and that the said Jesuit Fathers will be able to take of his Majesty ratification present in one year. In witness of which we have signed them, they have to affix the seals of our arms, and to compel by our Secretaries. Given at Quebecq, this twenty third of October, one thousand six hundred and ninety-nine.

Signed “Le Chevallier de Callières. ”

And “Champigny. ”

Sealed with the seal of their arms and countersigned

By Monseigneur, “Hauteville”

And By Monseigneur, “Andre. “.

And below:

EXTRACT from the Letter of the King to Sieurs Chevallier de Callières, and Beauharnois, Governor General and Intendant of New France.

His Majesty has granted also, that of the land of Sillery, demanded by the Jesuit Fathers, that it is against the rule that it has made itself no longer to give land of Canada to Ecclesiastical Communities.

Collated with the Original by us Intendant, in the said country, the twenty fifth of November, one thousand seven hundred and two.

Signed, “Beauharnois. ”

And below By Bishop Trehard. ”

TODAY, the Title of Concession and the extract from the Letter of the King, of which it is in the foreground, have been registered with the Registry of the Sovereign Council, following his arrest of that day, by means of the said registry at Quebec, this second July, mils seven hundred and three.

(signed) “Hubert,” with initials.

(The following was entered in English)

I do hereby certify the foregoing to be a true copy from the original, as on record in the Office of Enrollments at Quebec, in a French Register, intitled, “Registre d’Insinuation Cons. Sup. B. No.2” verso 137. Provincial Secretary Office.

Quebec 5th of April 1847

DDalz

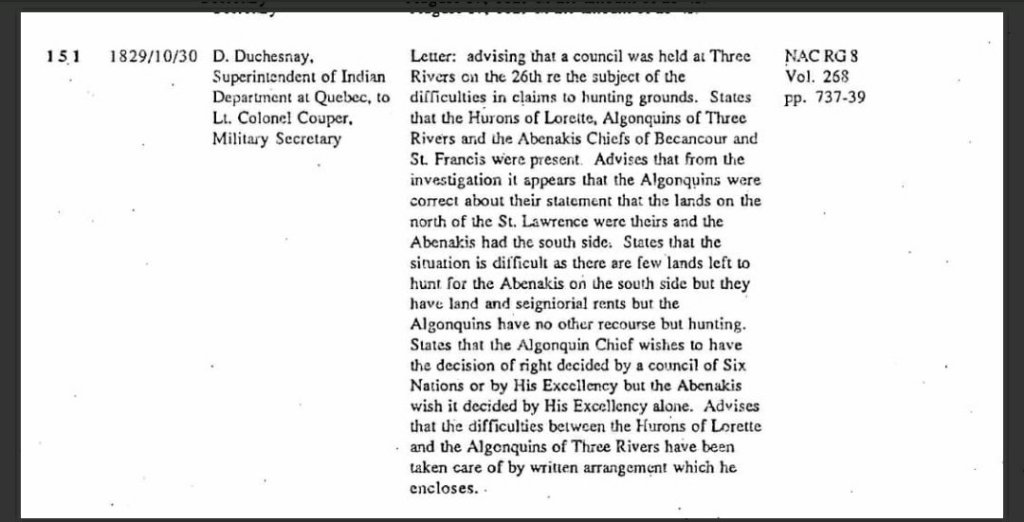

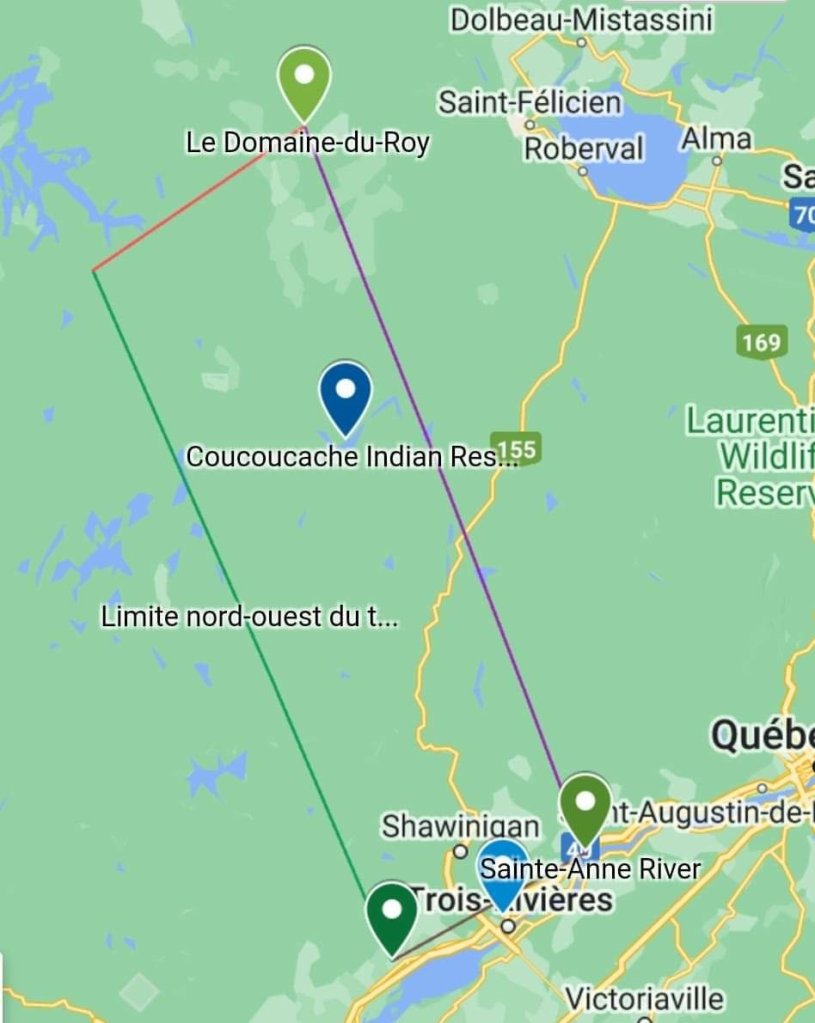

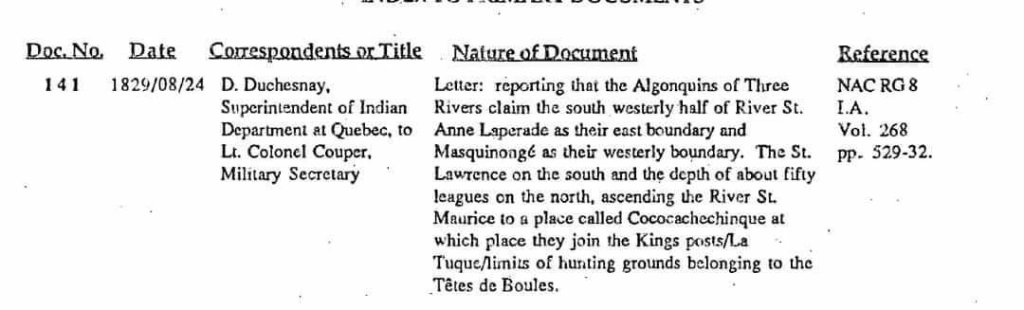

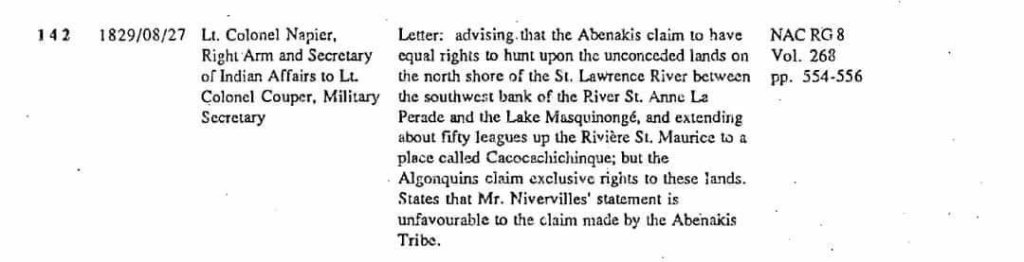

Sec